The Diary of Kohima

Tareen took out the pages of the manuscript of her father’s book from the bulky old Manila envelope and lay them on the desk. She glanced at the finished Bengali novel, which these pages had helped create and which sat on the other end of her desk next to the framed picture of her father.

That old photo, almost sepia, showed Abba in his uniform as a soldier in the British Indian army, a sparely built, good-looking man. How strange, she thought, that he was younger at the time the picture was taken than she was now.

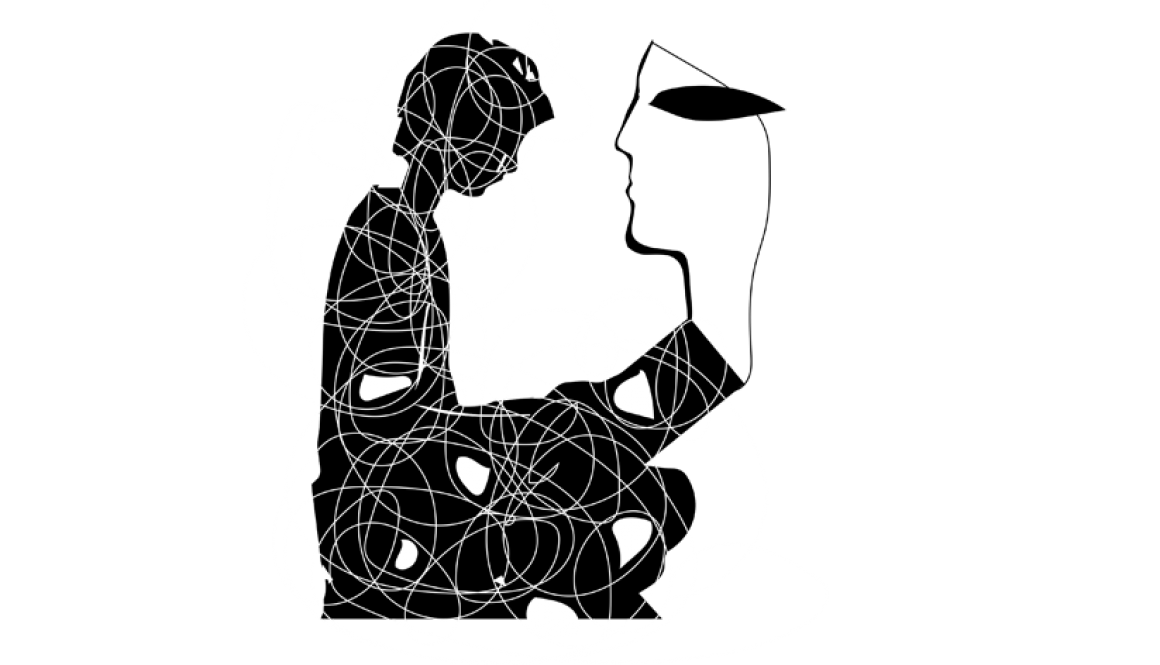

Somehow, throughout her life, this picture never seemed a true portrait of the father she remembered or knew. Now holding the manuscript of her father’s war novel “The Diary of Kohima”, she had a strange feeling that the photographed man was not the writer but the fictional character Lt. Ameen her father had created. Sometimes the truths of our selves are better revealed in our invented narratives.

Many years ago, as a young girl growing up in West Pakistan and learning to read Bengali at home while studying Urdu at school, she had read her father’s book as a duty to herself. She had not found it terribly interesting. Today, handling the pages of the actual manuscript, with its penciled corrections and editorial notes by her father’s publisher friend Zahoor made her see the book as a window into her parent’s life.

The envelope containing the manuscript also contained a few art works as suggestions for the cover. It contained an ink sketch that came closest to the one finally selected for the novel’s dust cover. It showed a convoy rolling down a mountain path and in the foreground, a sloe-eyed young woman in a sari looking on. That was Miss Shimui, the female character that her mother said she and Zahoor uncle had forced her father to flesh out and put in a prominent position not only on the cover but in the dry narrative.

Tareen picked up the manuscript and started to read. Again, she thought how like her Azeem Bhaiya the character was. Yes, Ameen in 1942 and Azeem in 1971 were similar. She hadn’t thought of her elder brother in a long time. Her handsome, idealistic brother. Who would have thought that a bookish, sensitive boy would have found his destiny in a war?

If life had turned out differently for Azeem, would he have written his account too? What kind of a book would that be? One day she would dream up his story. Today, she had to return to her father’s memoir-novel.

***

THE DIARY OF KOHIMA

By Shahabuddin Ahmad

(Dedicated to my wife Haseena)

I am sitting alone on the dark lawn of this Inspection Bungalow. It can’t be more than nine in the evening, yet the surrounding stillness feels like the dead of night. There is no other sound except for the distant howling of jackals beyond the hedges. The horizon stretches endlessly into the far off hills and the sky. Tonight, I feel my mind pulled far and away, to a world long gone…

The year was 1942. The Second World War was at its peak. In India, the war was concentrated on its North-East Frontier, where it shared its borders with Burma. To the north and west of Burma lay the Indian provinces of Assam, East Bengal, Manipur and Nagaland. By March 1942, the Burma campaign had suffered major setbacks and when Rangoon finally fell to the Japanese, the British were forced to abandon it and retreat homewards to Assam. The preoccupation of the moment was the defense of Assam, the eastern gateway into India, from further Japanese offensive pushing through Dimapur in the north, or the plains of Imphal in the south.

Against the wishes of family and friends, I, a university student, fully aware of the rising sentiments of nationalism raging through India against its colonial masters, nevertheless decided to join the British Indian army.

I had done all my thinking before, debated the pros and cons with my friends. The final decision was based as much on matters economic and practical—the bait of a good civilian job after the war, as on principles of honour. My country was under threat of attack from the Japanese which was more urgent than the long siege of the country from generations of British rule. I felt that the British in India were a spent force, anyway. I didn’t advocate using this crisis towards the mass struggle for freedom and sovereignty. In my opinion, those were political issues to be fought at conference tables rather than in the battle fields. I was one of the few who didn’t much care for the confused policies and ideals of the rebel leader Subhash Chandra Bose and his Indian National Army, which had joined hands with the Japanese and Germans in a nebulous strategy to weaken the colonial grip of the British. I decided that the urgent call of the day was the defense of my country, and I decided to fight for it even if it was under British leadership.

Once the decision was made, I felt a surge in my blood from the idea of dedicating myself to the cause of defending my land. The sentiments of a soldier are old and trite; however, they feel true to the young man when he starts out with his swashbuckling image. I too, imagined myself as a knight, the gallant Rajputro-prince on horseback of my childhood fairytales.

I went through the selection formalities of the recruitment commission, then joined the military training centre. I was no longer Muhammad Ameen, MA, Political Science, Dhaka University, but Cadet Ameen. The 6-month training course was thorough. Apart from rigorous physical fitness programmes, our minds were also drilled with a sense of discipline, duty and impeccable efficiency. I put my heart into becoming an officer and a gentleman.

A few months after our training, we went through the “passing out” ceremony, which was celebrated with much fanfare. Now my soldier’s life dawned with its first star twinkling on the shoulder of my crisp uniform. I was now a commissioned officer, a Second Lieutenant of the British Army.

I was immediately called to the Eastern theatre. All of Assam and Burma were now a war-zone. The Railway line ended at Assam’s Dimapur. From here a large highway runs south from Kohima in Nagaland and Imphal in the plains further south and into Burma.

This road was the only connecting route to send supplies and soldiers, and military convoys were passing ceaselessly. I joined a convoy carrying military rations and set off with them towards my unknown duty station. I didn’t know yet which would be my final destination: Kohima, Imphal or Kalewa.

Narrow mountain roads, hugging the steep mountainside, curved and snaked their way higher and higher. Frequently, we came across bridges with mountain springs gushing down the deep ravines far below.

All day, the convoy moved endlessly like lines of soldiers marching. Sometimes we stopped for rest. At one point, towards late afternoon, suddenly the convoy stopped. I heard a great deal of running back and forth and shouting of orders from the head of the convoy. Getting down, we discovered that a truck, from a previous convoy perhaps, or a solitary one, had fallen down the side of a mountain and was lying overturned at the bottom. Enquiring for details, we were told that the truck had hit the rails of the bridge, and that three men had been killed and one badly injured. Some of our men climbed down to offer help. The scene affected us all, but everyone tried to look composed as the wounded man, along with the dead were sent off to the CMH of Dimapur. As our convoy set off again, my driver shrugged saying that in these parts such accidents happened often.

Our convoy reached Kohima safely. Here we were to have a half hour’s rest. Getting out of the car, I stretched my legs, walked around a bit, breathing the freshness of the air and observing my surrounding. I looked back at the winding way we had come up to this ridge on which the little town of Kohima stood, 5000 feet high on a saddle in the Naga hills. It looked little more than a scattering of thatched huts among banks of rhododendrons and a wilderness of jungle-green and rocks.

In a while the Convoy Commander asked for me and gave me a signal message that he had just received. I read: “Lt. Ameen will report at 601 I-F-P-D.” On enquiring I was told that 601 Indian Field Petrol Depot was in Kohima itself. I proceeded immediately to report to the unit. There I heard that the former Officer Commanding had suddenly been transferred and I would have to take over his duties temporarily.

This depot covered almost one square mile and was protected by the mountains and barbed wires. My living quarter was in a tent on a small hill. The canvas tent was pitched on bamboo poles and stilts on a shelf of cleared land before it sloped down or up to be claimed by the mountain vegetation.

The next day, the soldier assigned to assist me, Subedar Sunder Singh, having taken care of all my immediate needs, showed me around the place. He told me about the violent 64-day battle that had taken place at Kohima a year ago. I knew every detail about it, of course. Later, historians of World War II would designate the Battle of Kohima as one of the most crucial and bloodiest battles fought in the East. For 14 days and nights the defenders of Kohima held the bridgehead to India and managed to stall the Japanese advance.

As I looked around, I saw that the surrounding areas of Kohima bore visible scars of that battle. Hillsides were in tatters; plants had been hacked or singed; and scraggly bushes hung like disheveled, hopeless heads. In the distance stood some trees that had been blasted by explosion and now the stumps stood ghost-like. Near my tent were scattered the detritus of bullets, shells and pieces of grenades. Dark patches of earth bore the evidence of fires and flames. There were craters in various spots.

Now everything seemed to be under control both here and at Imphal, but Kohima was still crucial to the continuing success of the Allied forces in what we would later realise were the waning days of the war when we were chasing the Japanese.

That first day, Subedar Singh showed me where the petrol barrels were hidden at the foot of the hills, under bushes and covered by tarpaulin. From the mountain top nothing could be seen. The barrels of “aviation spirit” for air-crafts were even better concealed. I was shown also the guard posts equipped with fire extinguishers.

One day I went with Subedar Singh to see the local market, the Boro Bazar of Kohima, a mile away from our depot. On the way, we saw Naga coolies, men and women, old and young, tirelessly working. The mountain roads, which were of great military importance, needed constant maintenance. Drainage for rainwater, leveling of roadsides, and the placing of warning rocks painted white at the edges of steep curves whose sides fell away to deep ravines: there was a lot to do, and these hardy tribal people were constantly working.

Our road descended to the bazaar. Apart from the colourful market, there sprawled before us the habitations of the Naga locals. This was the Kohima Civil Lines.

On the way back from the bazaar, Subedar Singh asked me if I wanted to see the Japanese cemetery. I nodded. The day before, I had gone to see the cemetery where our dead were buried. This was on a plot near the tennis court behind the District Commissioner’s house at the edge of Garrison hill on a high ground with a view of Kohima village terraced below.

On the day I went to pay my tribute at the cemetery, the sun was mellow, the breeze in the bushes of wild flowers fresh, giving the place a serenity that was in contradiction to the violent history of the place. A year ago, this very tennis court had seen days of slaughter and fierce combat against the Japanese, which was our last line of defense between the Japanese and the British lines.

In fact, Subedar Singh had shown me the burnt trunk of the tree from which enemy snipers had attacked the British forces as their desperate last stand. I also noted the burnt-out shell of the Lee tank that had been pulled up by the British soldiers over a steep gradient to fire into the enemy bunkers, finally bringing the Japanese to their knees.

The freshly dug graves belonged to brave soldiers from the Durham Light Infantry, the Royal Norfolk Regiment, the Royal West Kents and from the Assam regiments. The dead were a mixed brotherhood: there were Indians from Bengal, Assam, Punjab, Southern India. There were local Nagas, Australians, some Americans, and British from every corner of Britain.

In various languages and accents and faiths the soldiers had shouted out invectives, screamed in agony, and cried out to their families, their loves and their gods before they fell here.

I stood before them, bareheaded and bowed, without any specific prayer but in a deep silence in which I heard the birds and insects and the breeze in the trampled jungle, as well as, every now and then, the voice of the villagers working steadily on the Dimapur road somewhere below, in a world still not finished with war.

The Japanese cemetery was just behind our Supply Depot. On a few plots of leveled land the graves were lined up in military precision like soldiers on parade, disciplined even in death. On one grave there was a plaque that said: “Unknown Japanese soldier”.

I tried to imagine him, this crafty and ruthless enemy who had adapted himself well to the terrain. His uniform was light, his boots strong and rubber soled. He carried only a water bottle, a ball of rice, and some scraps of dried fish. His weapons were automatics suited to the close-quarters encounters of the jungle, grenades, light machine-guns, and two-inch mortars. If he thought the roads were defended he avoided them, hacking his way through the jungle instead or following little-known paths for attacking and ambushing.

It was said that the first news that the Japanese were attacking came when defending troops in the forward positions could get no reply from their headquarters in the rear. Yet, this hated and feared enemy too, had fallen, and in death become just another dead soldier, not unlike the ones he had killed and who were buried in the Allied cemetery high on Garrison hill, where on a tennis court a game of life and death had been played out.

As I straightened up I took off my cap and saluted in military fashion. Subedar Singh looked at me for a second and then followed my example. I turned away from the graves and towards him, explaining my action.

“Subedar Singh, I respect even my enemy because he was a soldier doing his duty to his country until his last breath. He gave his life for a principle and to die in battle is a glory for any soldier.”

After that self-conscious speech we stood for a moment in awkward silence, not at all sure we were convinced, but with a feeling that some verbal ritual of honour had been observed, like a prayer for our own selves.

[Excerpted from the novel-in-progress “The Ninety-Nine Names for Being”]